I had the most amazing time interviewing Dr. Sara Harrison Sohmer. Even before we launched into our conversation about her mother, we talked for hours about her fascinating dissertation on Anglican Missions in Melanesia (1850-1914) that she completed at the University of Hawaii. Below is the story of her mother.

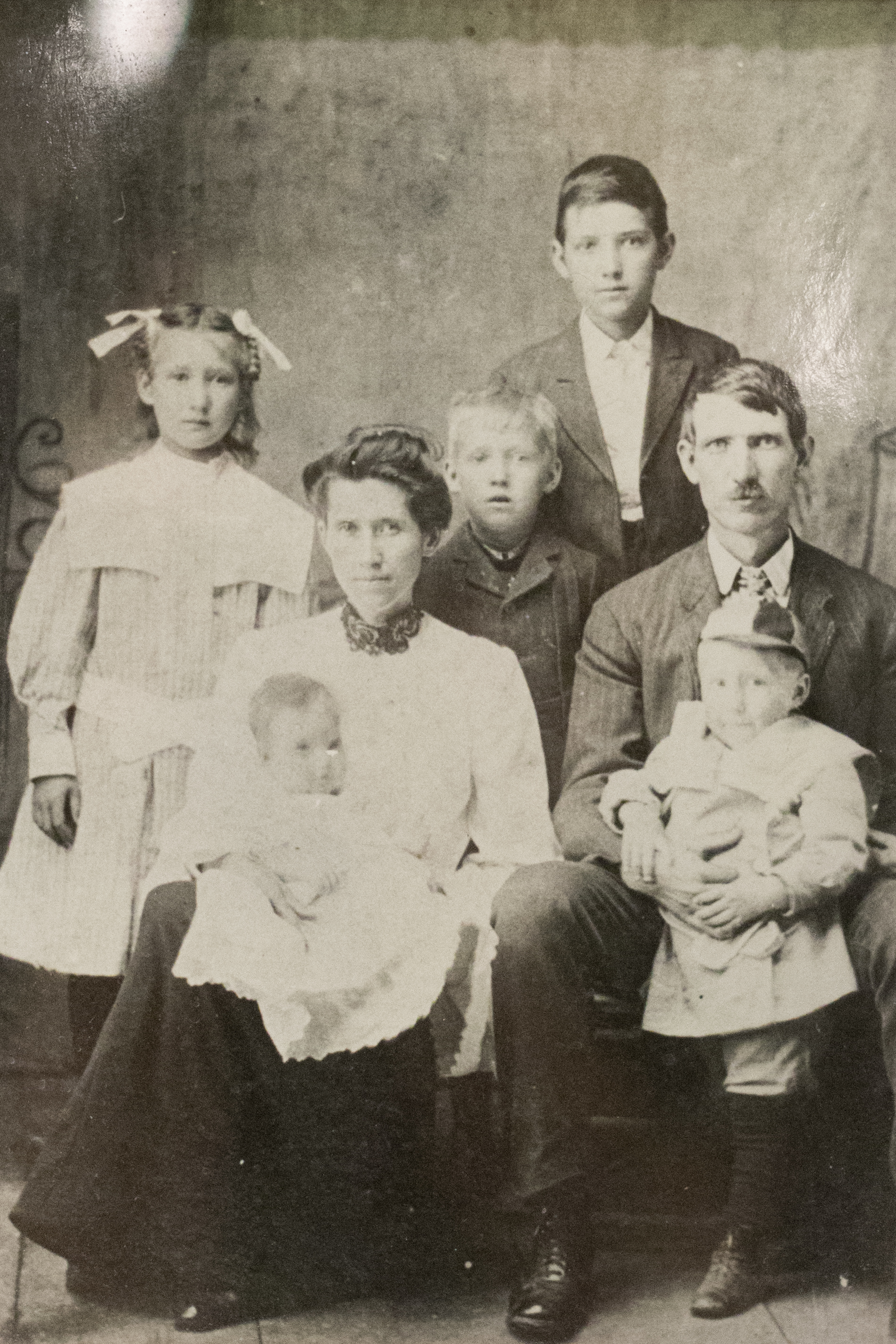

Sara's mother as a toddler.

“This is picture of my mother as a toddler. She was always getting out of her shoes. Little country town in east Tennessee. Always stepping on something. Swollen infected feet all the time. A travelling photographer came through and they couldn’t wait for her foot to heal. But I love that she's only got one shoe.”

“What was the name of the town?”

It’s a little town called Oneida. If you go due north from Chattanooga, you hit Kentucky. The last town in Tennessee is Oneida. It had a whopping population of 3000, after they incorporated the top third of the county. They just decided you're all living in town. It used to have three high schools that consolidated into one later. It was just the same families who had been there since the cooling of the earth's crust.”

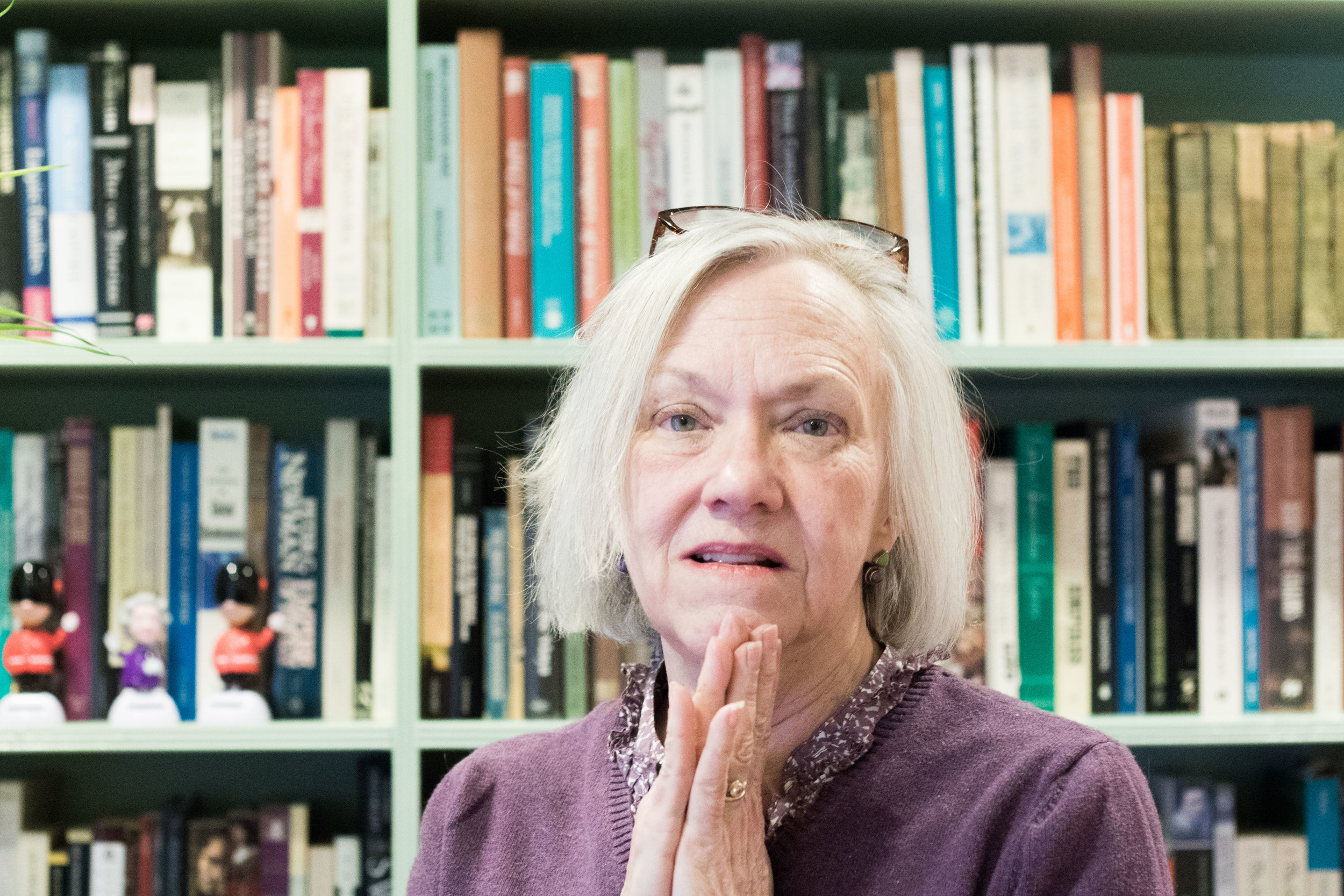

Sarah's grandmother is the little girl in the top left.

“This is my grandmother's family. It looks like “American Gothic,” doesn’t it?

“When was this taken?”

“My grandmother was born 1903, 1904 - the first decade of the twentieth century. She was the baby. So this would have been, I imagine, judging from the clothes - not quite WWI - sometime between 1900 and WWI. Her mother was very conservative. She was illiterate. She would sit on the front porch and turn the pages of her Bible but she couldn’t read it. My great grandfather had a country store - but my grandmother was the smart one, and her school teacher told him that she was too smart not to move on to school. He put her a train the next day, all by herself, at 13 years old. So of her whole family, she was the only one - I’m not sure if her other siblings even went to high school. Scott county people, you know?”

“I’m surprised that he decided to educate his daughter. It looks like he had one son?”

“Oh, I remember Uncle Henry. He never amounted to a great deal, actually. My great grandfather had the sense to realize that she was smart and when the teacher told him, he just packed her off. As people went in the village, he was fairly prosperous - he had the store, he raised horses for people who worked lumber, and things like that.”

Sara's grandfather is the tall boy in the back.

“My grandmother and grandfather, they were the exceptions. It’s interesting, she was the baby, he was the oldest. His father had every intention of him working the coal mines, or lumber, as the oldest boy he was going to help support the oncoming kids. Nine, I think, although they lost a couple. Again, everything turns on so little - my grandmother had the teacher that said, ‘No, send her on.’ My grandpa had an uncle who told his brother, ‘Chester's far too bright for you to work him to death, you need to send him to college.’ He was the one, and she was the one. They emerged.”

“How many children did they have?”

“Just the two. And both girls. My mother and her sister. My mother went to Berea college, my aunt went to junior college in west Tennessee. My mother was so young when she finished undergraduate school. She would have been barely 20, and looked much younger. My grandfather said, ‘Why don't you try and go to graduate school?’ She did - she went to the University of Tennessee. She met my father there when he was in undergrad.”

“I didn’t realize women could even go to graduate school in the 30s?”

“She got her master's in home economics. But home economics then - my mother was always certified when she was a teacher. She was certified to teach science. With a master’s, in home economics she studied nutrition, and she had plenty of chemistry and biology. I was always struck by what my mother knew. She could do math - which was totally mysterious to me - all of them could. We lived with my grandparents, and we had three very smart adults on our case, all the time. When we were small and people asked my brother and me what we want to be when we grow up. We always said, ‘We're going to college.’” My grandfather collected degrees. My mother had the first masters. My aunt got one later on. My undying regret is that my grandfather died before I had my PhD. He would have so loved it.”

“Everything turned on so little. When i think of how things could have gone. There was a recent survey of the economic scales of all the counties of the continental US. In terms of a poverty index, if number one is the worst thing you can be, my county was 16th out of more than 3000.

“Is it about the same now as it was back then?”

Economically it was a bit better then. In the sense that there were raw materials - coal and timber, which has long since disappeared. I remember as a kid wondering what we did as a county. The land is not good for prosperous farming. You can hang on. Teaching was a good job - a very good job. My grandfather first taught shop in school, and eventually was president of the local bank, which was very substantial. An auto dealer was very substantial. In many respects it is more deprived now than it was back then.

“Can you tell me about your father?”

Sarah's mother and father.

“My father died in the Philippines at the very tail end of WWII. I was just a baby when he died, and I never met him. He was from west Tennessee. Which is like being from a different nation. Anyone with a long association with Tennessee will tell you, ‘I'm from west Tennessee, middle Tennessee, or east Tennessee. West Tennessee was cotton country - it's the south. The middle is similar. East Tennessee is Appalachia. Just by way of establishing difference, when I was a kid, there was not a single black person in the county. Not true of cotton country. My father's family in west Tennessee were tenement farmers. His father farmed and was a carpenter. He was one of five. He went to college because his mother was determined. She mortgaged her house without telling her husband to send her boy to college. It nearly killed her when he died.”

“How old was your mother when she was widowed?”

“She was 26, 27. She brought me home to my grandparents’ house, and we never left. I suppose she might have considered remarrying. She didn’t. Not until after my husband and I were married. Our entire existence was the grandparents and my widowed mother, and we thought that was entirely normal. We didn’t know, and she was so much fun. We loved her to death, and she just was good to be around. It never occurred to us that mother might not have had a wonderful life.

“I just really think, and have always felt, that everything about my life that has remotely been worthwhile, had so little to do with me and everything to do with this, and these people, and especially my mother. So many women went under from that experience. And she not only didn’t, but she was just fun to be around. Not to say she was a pushover - God, no, oh my word. We didn't have a chance of going wrong. They knew we were in trouble before we even thought of it. She was such a good grandmother as well.”

“It must have been really interesting to have basically three parents?"

“My mother said her mother only stepped in twice to say no to her parenting. ‘She never told me what to do with my children. And I'm living in her house. I've never forgotten that.’ Once was - as mother was trying and struggling to nurse my brother, and she was so tiny, and he was a huge baby, and my grandmother went to town and brought bottles and said, 'We're not doing this anymore.' And the other time, my brother was just a little toddler, and he'd been into something, and my mom was really after him about it, and my grandmother said, "I'd back off. You're going to teach him to lie to you.” That’s twice in 20 years, that she ever said anything about parenting. These were amazing people.”