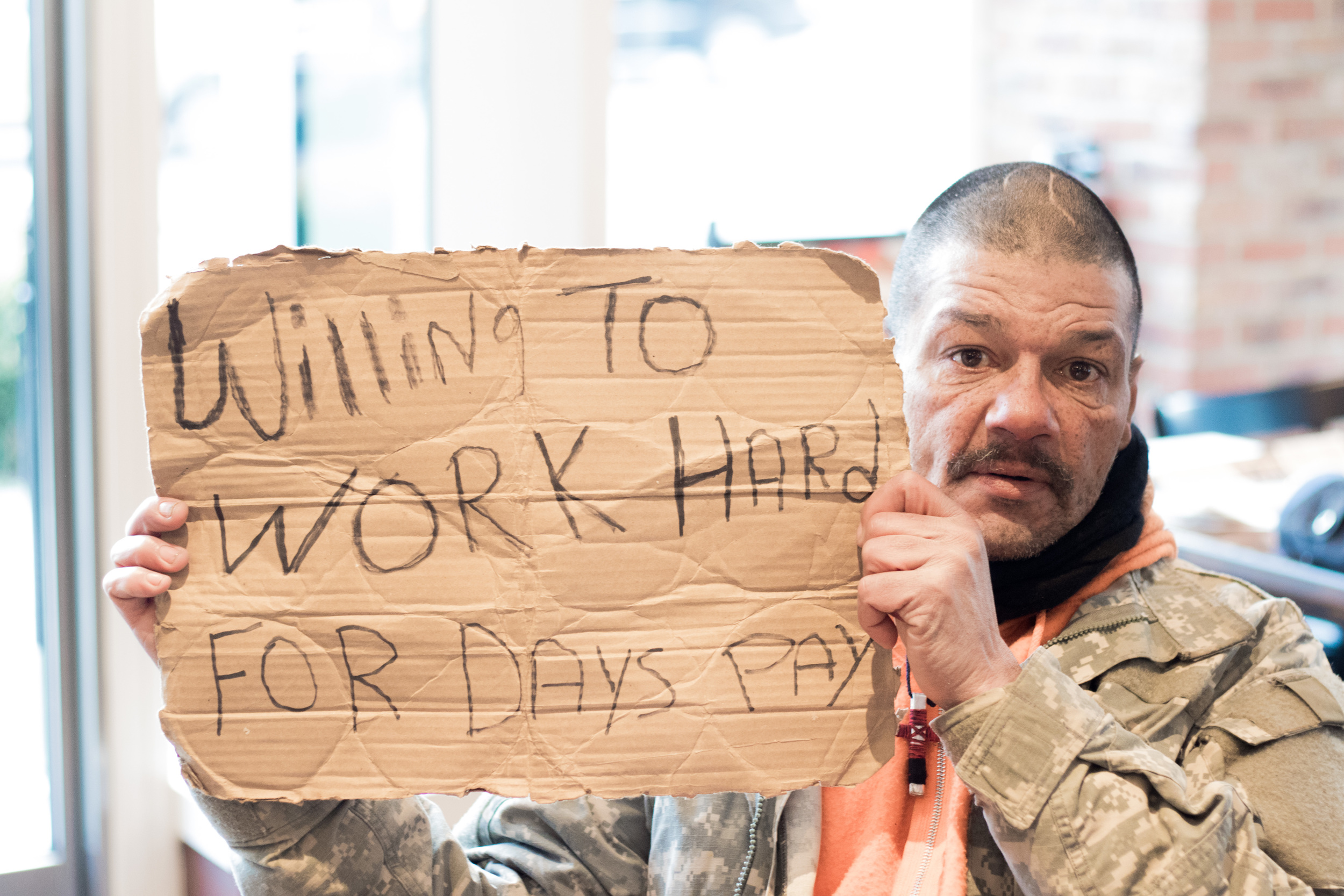

On a morning so cold that no one wanted to step outside, we found Gizmo standing at an intersection near the Capitol. He held high a sign asking for work, the cardboard placard grasped tightly as possible between frozen fingers. He told us his full name and then asked if we would go by his nickname.

“I’ve been waiting. I’ve been waiting for someone to come over, say hello. Just smile,” he said, greeting us with a smile of his own.

We found a reprieve from the bitter wind in a coffee shop nearby. “I cross the street like that my whole life—no crosswalks,” he grinned as we walked across the street, nearly deserted despite the rush hour.

We talked about other lines, too. “You know what a B&E is? Breaking and entering. I fell once, really far. My foster brother thought I was dead and they cut my clothes off at the ER. I was pieces. I still got the scars.” Gizmo lowered his head so we could see the lines patterning his skull like continents.

“I disappeared when I was nine. Nine for two more months, after my mother died. We were in a crash and they got her out of the car to the hospital. She was there a few days. They wouldn’t let me see her. I just wanted to say goodbye and I couldn’t.”

His looks away as he speaks of her, his mother. “She always told me, ‘You don’t let anyone put their hands on you; don’t let anyone hurt you.’ I stabbed a policewoman when I was just six; she’d come up and grabbed me and I was scared. I’d found this knife on the street and it was cool, you know? This black object with a blade that could pop in and out. She grabbed me and it hurt and so I just slipped the knife in. They locked me up. My mother, she came to the station and said, ‘You let my son out. What was he supposed to do? You’re surprised? You hurt him, so he did what I said.’ I don’t let anyone go hurting me, never.”

“My mother, she used my full name. She’d use it to make a point. But I got the name Gizmo because of the movie. You know the one? Because a gremlin gets into everything, and that was me.” He laughed and shook his head, remembering to himself for a moment.

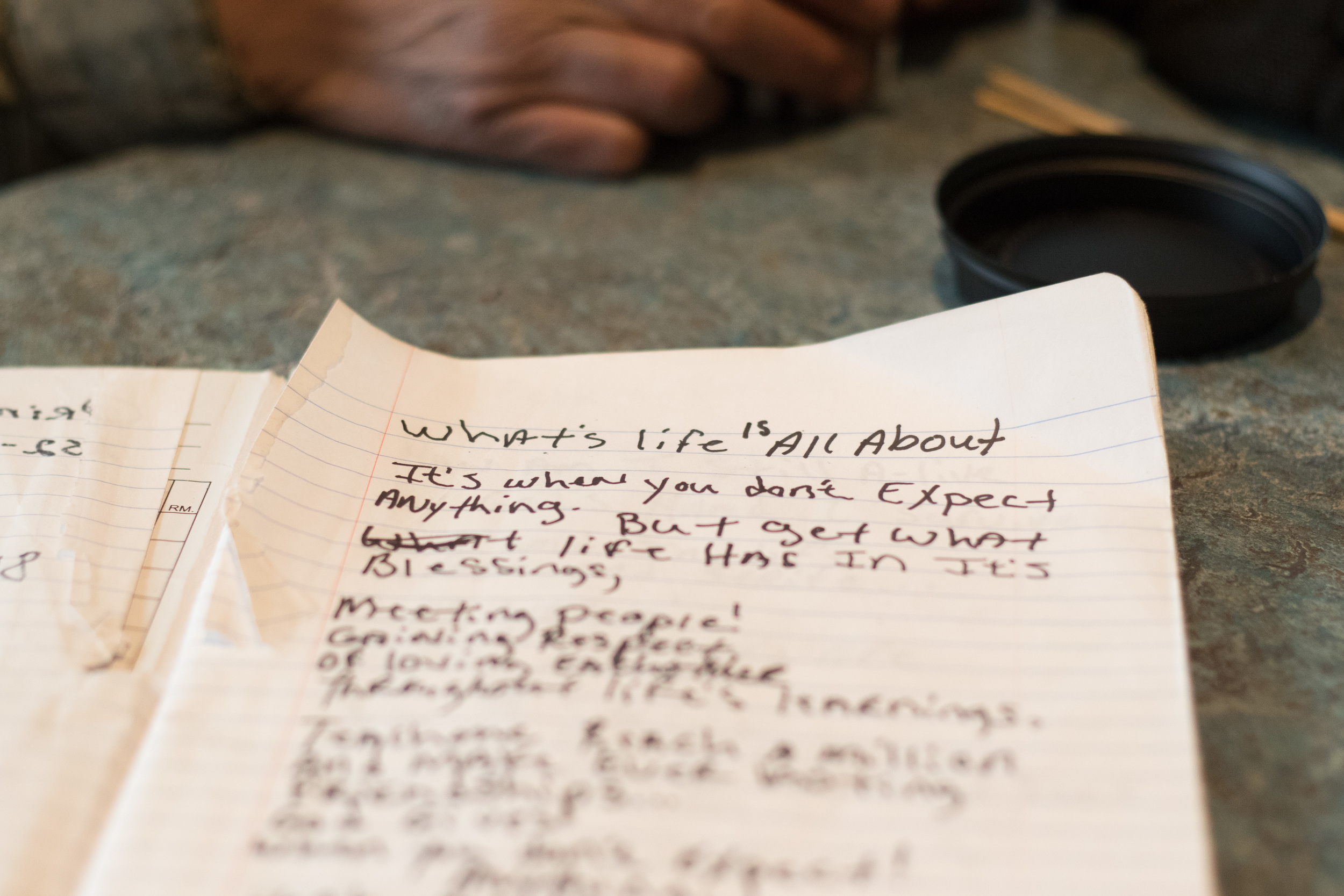

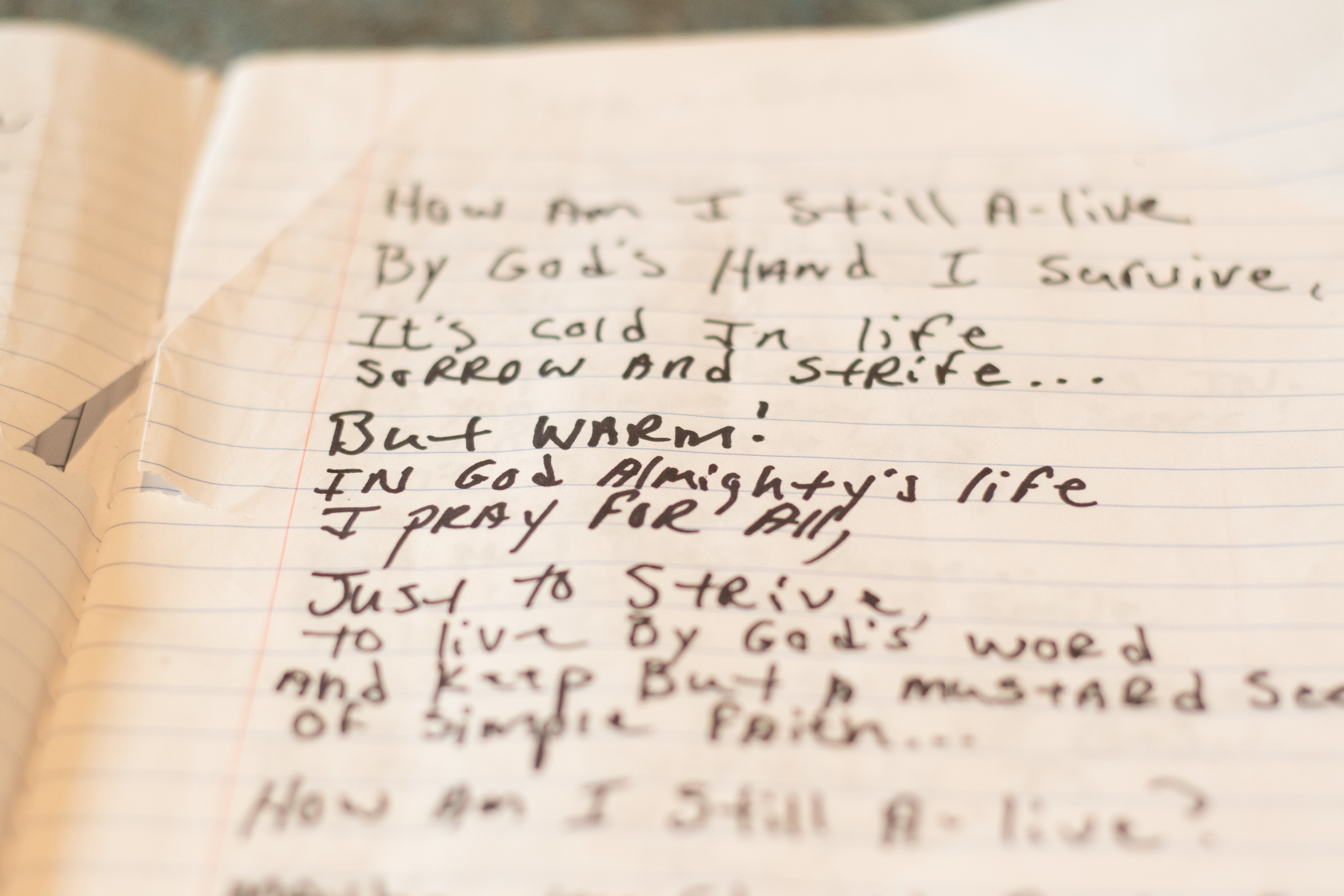

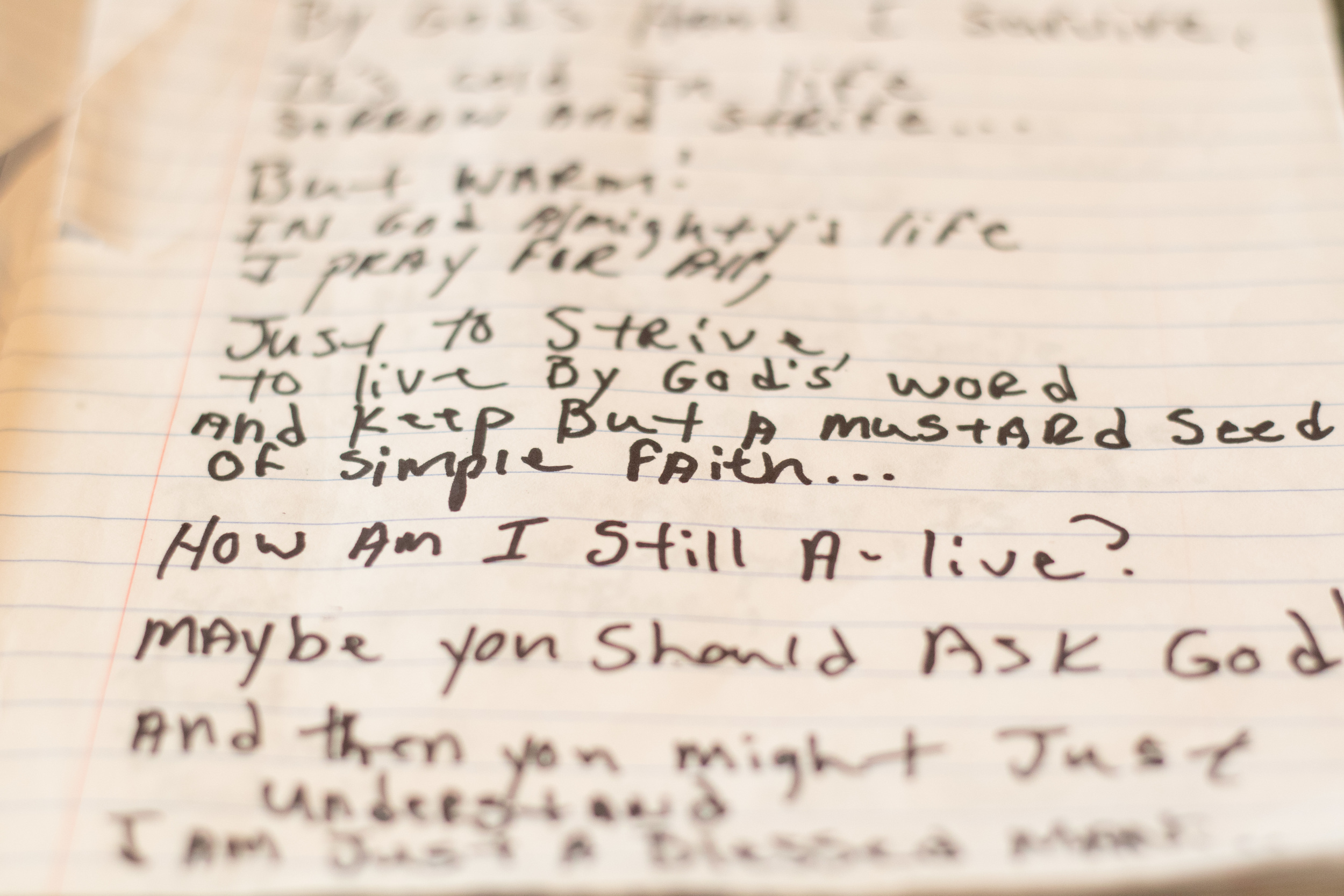

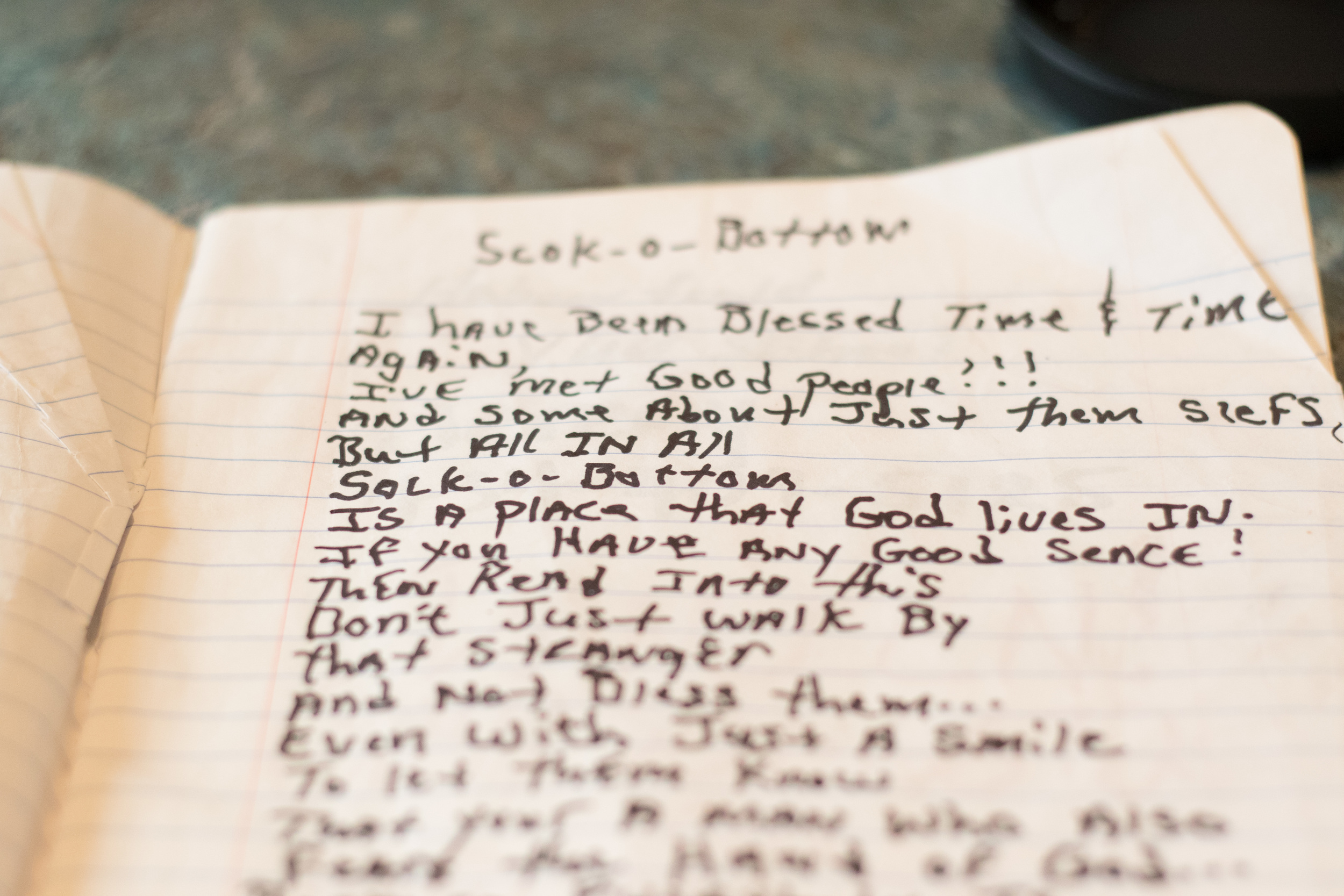

“I’m here, running from my past. I’m a former mobster. 30 years in prison, I was. I write now. I’m working on a book. I write poetry. I make my way.”

“I sleep over by the Supreme Court until I can get back to New York. I’d sleep on the steps of the White House if I could get in, I would. I’d like to see them tell me to leave because I’m not just half Portuguese, I’m half Native American and I’d tell them, ‘You leave. We were here first.’”

He laughs at the idea for a moment and then goes silent, glances at the broken door beside us where the sixth person in a row is rattling the glass before seeing the sign and giving up.

“I should speak three languages,” he sighs, shaking his head. “I wish I did.”

As we gather ourselves to leave, he leans towards us. “Promise me one thing.”

He doesn’t wait for us to answer, but rushes on. “Promise me you’ll learn something new every day. Every day. Then you’ll never be without something. That’s my challenge for you.”

Guest Writer: Heather Hill

Heather Hill is the Assistant Manager of donor acquisition & digital fundraising at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She is a graduate of Houghton College, and Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is the Human Rights Co-Chair of the United Nations Association of the National Capitol Area, and you can find her performance reviews on MD Theatre Guide.